The Method of Moving Frames for Surface Parametrization

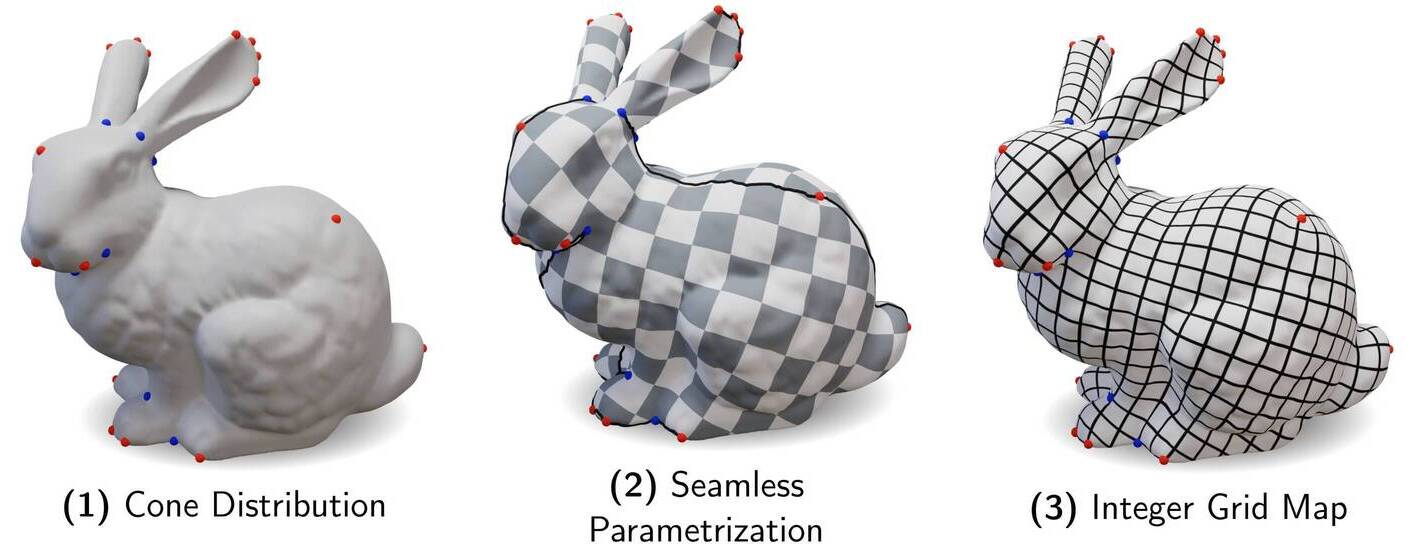

Quadmeshing with Seamless Parametrization

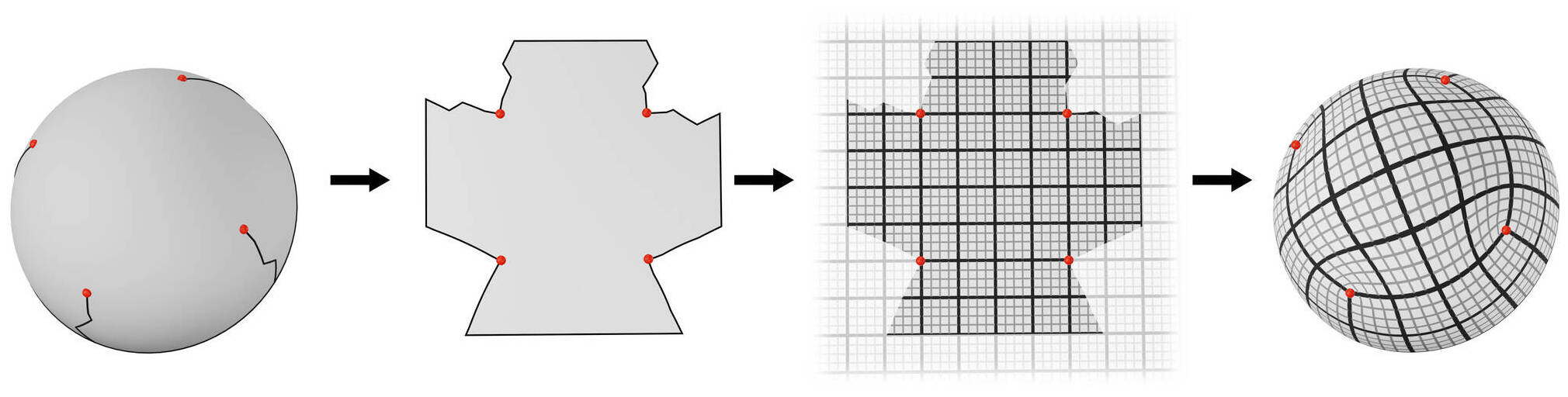

Computing a high-quality quadmesh of a given object is a challenging task of geometry processing, with applications in both computer graphics and numerical simulation. A promising approach to solve this problem is to rely on a parametrization, that is a flat representation of the considered object. The idea is to overlay a grid on this parametrization which will then be pulled back onto the surface to form the quad layout. For this, the parametrization needs to have very specific properties, namely be an (integer) seamless parametrization, or integer grid map.

Figure 1. The parametrization-based approach enables the computation of a high-quality quad mesh. The idea is to compute a flat represenation (parametrization) of the object, over which a grid is overlaid before being pulled back onto the surface. However, the parametrization needs to satisfy very specific constraints for a quad layout to be extracted.

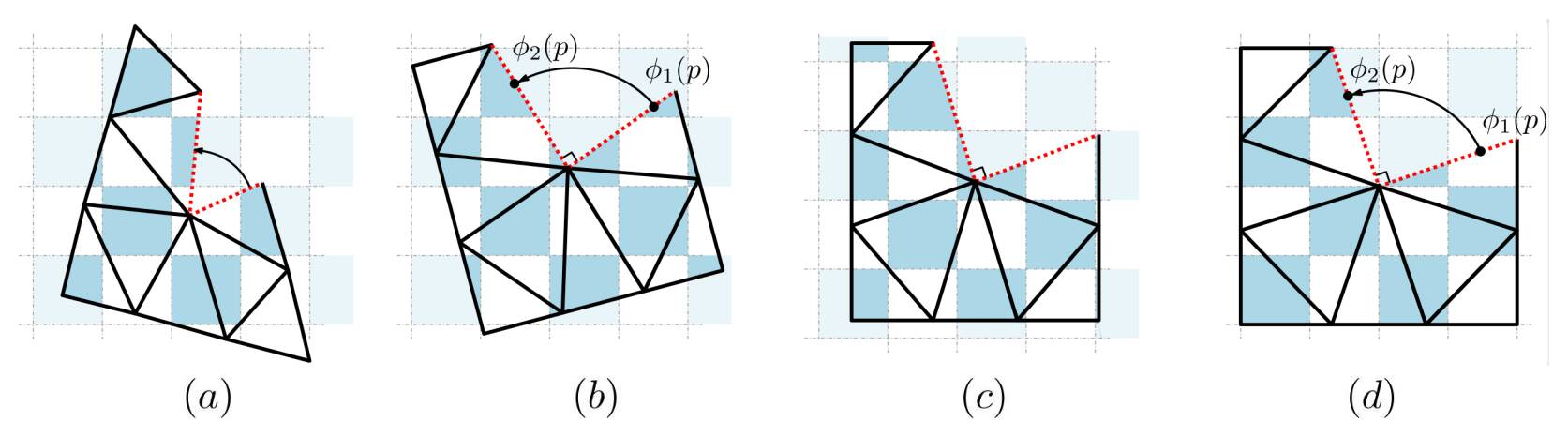

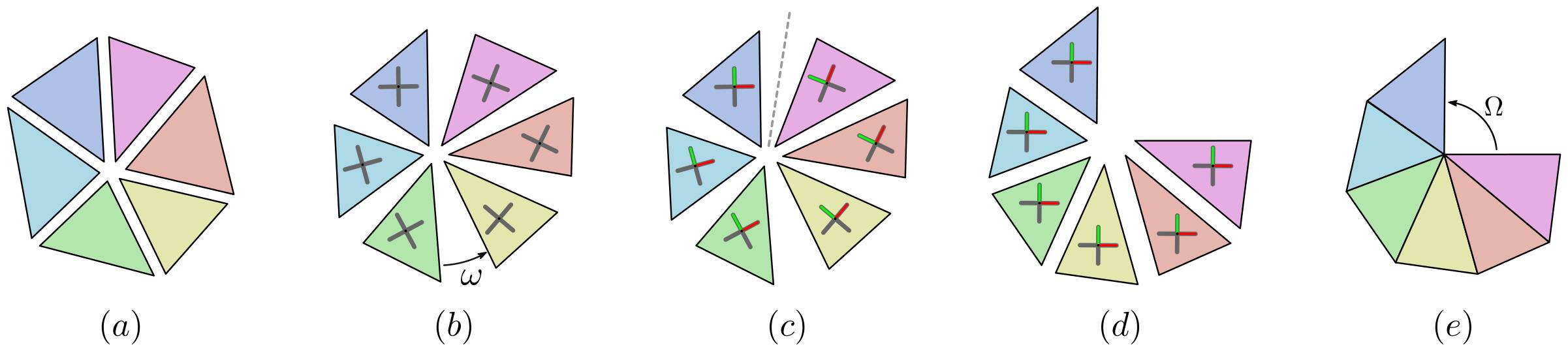

Let $M=(V,E,F)$ be a triangle mesh. A parametrization of $\phi$ is a mapping from $M$ to the plane $\mathbb{R}^2 \cong \mathbb{C}$. In practice, such mappings are represented by the coordinates in the place of each triangle corners, or, equivalently, as a linear transformation per triangle (Fig. 2a). In other word, having $\phi$ mapping a triangle on the surface to a triangle in parameter space is a commonly applied restriction.

A seamless parametrization is a parametrization with two additionnal properties:

- Across a discontinuity of $\phi$, two versions of the same edge should match up to some rotation of angle $k\pi/2$ and some arbitrary translation (Fig. 2b)

- Any boundary curve should be axis-aligned in parameter space (Fig. 2c)

To get an integer grid map, that is a seamless parametrization aligned with the integer grid, we require that the translations across discontinuities have integer coordinates (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. The different properties of a seamless parametrization. (a) Piecewise-linear parametrization. (b) Rotationally seamless parametrization. (c) Boundary-adapted seamless parametrization. (d) Integer grid map (quantized seamless parametrization)

When working with a seamless map, the exact location of the discontinuities (seams) of $\phi$ do not matter. What matters is where they end. Those ending points are called cones or singularities. In short, these points are where the curvature of the original mesh is concentrated as multiples of $\pi/2$. They will correspond to irregular vertices in the final quad mesh.

Computing an integer grid map is a challenging problem to formulate and solve in one go. This is why most state of the art method split the problem into several steps:

- Compute the position of the cones;

- Compute a seamless map that conforms to the cone distribution;

- Deform this seamless map to recover an integer grid map.

Figure 3. The usual parametrization-based meshing pipeline. As the problem of computing an integer grid map is too challenging to be tackled directly, state of the art method split it into several steps. While mostly successful, this approach is not without downsides.

Although it provides good results most of the time, splitting the problem has also brought its own issues. Firstly, as problems are solved indepently, greedy choices are often made at some step that invalidates the result of the next step. For instance, not all cone distribution can yield a valid seamless parametrization. Moreover, the distribution of cones on the surface has a clear impact on the parametrization’s distortion and the quality of elements in the final quadmesh. Determining the cones before computing the mapping prevents a method from taking advantage of this connection. This is why we propose an optimization that simultaneously computes a cone distribution and a seamless parametrization, thus merging the two first steps of the pipeline in a single one.

The Method of Moving Frames

The method of moving frames is a general framework developed by Elie Cartan to describe local deformations in differential geometry. At its heart is a set of structure equations which linka local deformation field with the local frames of reference. In this work, we extend the method to singular frame fields, allowing cones to appear, and apply it to the computation of seamless parametrization of triangle meshes.

Face-based vs Vertex-based Discretization

As the theory of Cartan deals with smooth manifolds, one first need to discretize it to be used on surface meshes. There are at least two ways of doing it, both with pros and cons:

- In the article, we describe a “dual” vertex-based approach, where frames are located at vertices of a mesh. Only this approach garantees injectivity of the final parametrization (as it prevents double coverings around vertices).

- Here, we present a simpler face-based approach, where frames are located inside triangles. This discretization is simpler to understand and implement, but theoretical garantees about injectivity cannot be drawn anymore.

In our implementation, both versions are available.

The Structure Equations

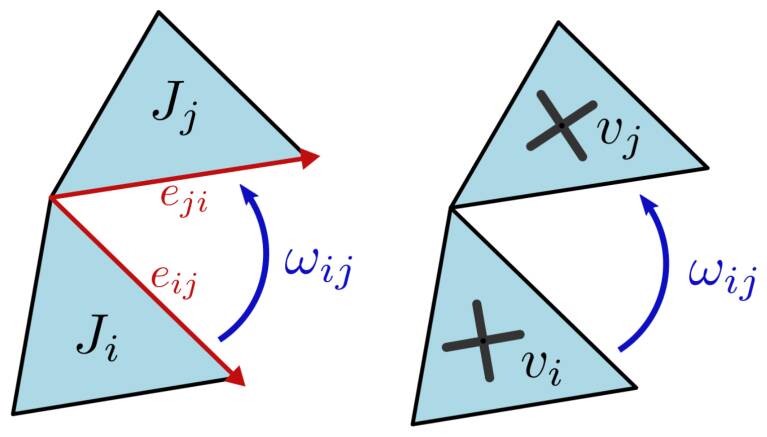

Let $M=(V,E,T)$ be a manifold triangle mesh. To express Cartan’s structure equations on $M$, we need to define the following variables:

- A Jacobian matrix $J_t$ per triangle $t \in T$, which will represent our parametrization $\phi$ as local linear deformations

- A $1$-form $\omega \in \mathbb{R}$ per edge

- A frame per triangle $v_t \in \mathbb{C}$ per triangle $t \in T$ that satisfies the symetries of the square. We use the classical power vector representation

Figure 4. Notations and variables of the parametrization problem

Given these variables, Cartan’s structure equations can be expressed as follows:

$$\left\{\begin{align} \exp(\imath \omega_{ij}) r_{ij} J_j e_{ji} &= J_i e_{ij} &\text{ (First Structure Equation)} \\ \exp(\imath \omega_{ij})^4 r_{ij}^4 v_i &= v_j &\text{ (Frames Regularity)} \\ \det{J} &> 0 &\text{ (Local injectivity)} \end{align}\right.$$

where $r_{ij}$ is the parallel transport between triangles $i$ and $j$ (some precomputed fixed rotation to account for change of local bases).

Cayley Transform

To avoid optimizing through the exponential in the above system of equations, we make a change of variables. Instead of working with an angle $\omega$, we work with $\hat{\omega} = \tan{\omega/2}$ and apply a Cayley Transform:

$$\exp \left( \imath \omega \right) = \frac{1 - \imath \hat{\omega}/2 }{1 + \imath \hat{\omega}/2}$$

which means that the equations are transformed as:

$$\left\{\begin{align} (1 - \imath \omega_{ij}/2) r_{ij} J_j e_{ji} &= (1 + \imath \omega_{ij}/2) J_i e_{ij} & \text{ (First Structure Equation - Cayley)} \\ (1 - \imath \omega_{ij}/2)^4 r_{ij}^4 v_i &= (1 + \imath \omega_{ij}/2)^4 v_i & \text{ (Frames Regularity - Cayley)} \end{align}\right.$$

This system of equation per pairs of triangles is then fed into a Levenberg-Marquardt optimizer in order to find a solution in terms of $J,\omega$ and $v$.

Parametrization Reconstruction

After the optimization, we have a set of linear transformations $J_t$ per triangle. If the structure equations are satisfied, the transformed triangles can be assembled back in a seamless parametrization following these steps:

- Reconstruct triangles independently by applying their matrix $J_t$ to their initial coordinates;

- Recover a basis $z$ per triangle from the power vector $v$ by finding the smallest symmetry rotation along a spanning tree;

- Rotate each triangle with relation to their respective bases;

- Recursively stitch adjacent triangles along the tree.

By doing so, singularities naturally appear as predicted by the $1$-form $\omega$. Note that the seamless parametrization does not come from the frame field variables in a classical integration procedure, but rather from the Jacobians.

Distortion minimization

As Jacobian matrices of the parametrization are available during optimization, one can try to minimize some distortion criterion alongside the structure equations to bias the optimization towards certain kinds of parametrizations. Basically any smooth function of the Jacobian matrices can be optimized in this manner. Some interesting functions are:

$$\begin{align} \mathcal{D}_{\text{Conformal}}(J) &= \sum_{t \in T} \left| J_t - \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} J_t \right|^2 \\ \\ \mathcal{D}_{\text{Isometric}}(J) &= \sum_{t \in T} | J_t^T J_t - I_2 |^2 \\ \\ \mathcal{D}_{\text{Area-preserving}}(J) &= \sum_{t \in T} | \det(J_t) - 1 |^2 + \varepsilon \mathcal{D}_{\text{Conformal}}(J) \end{align} $$

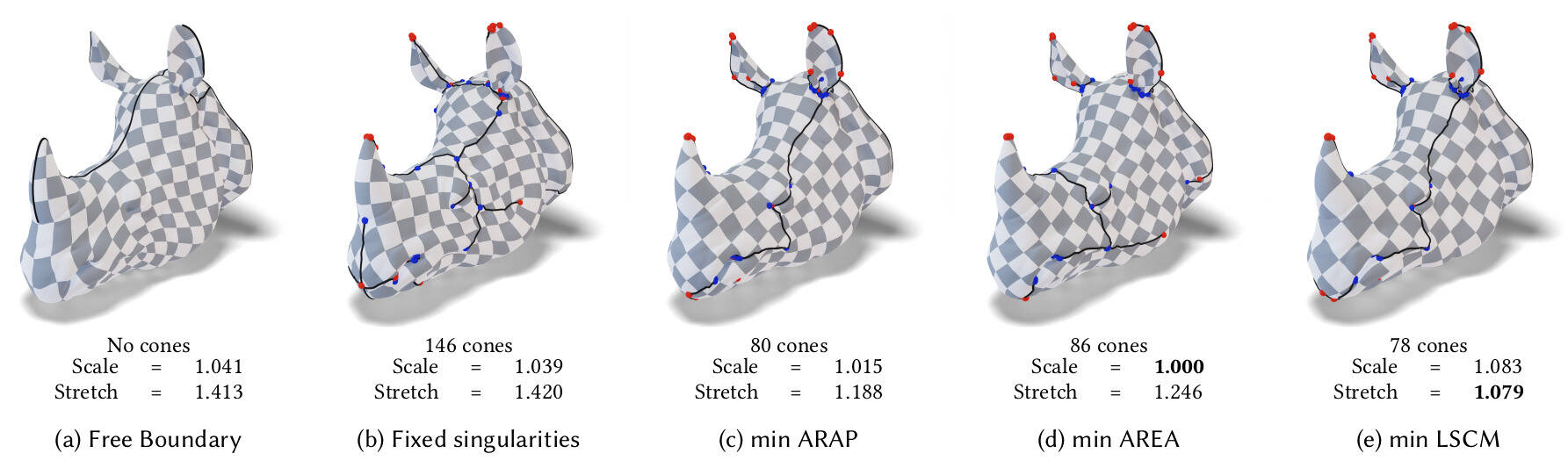

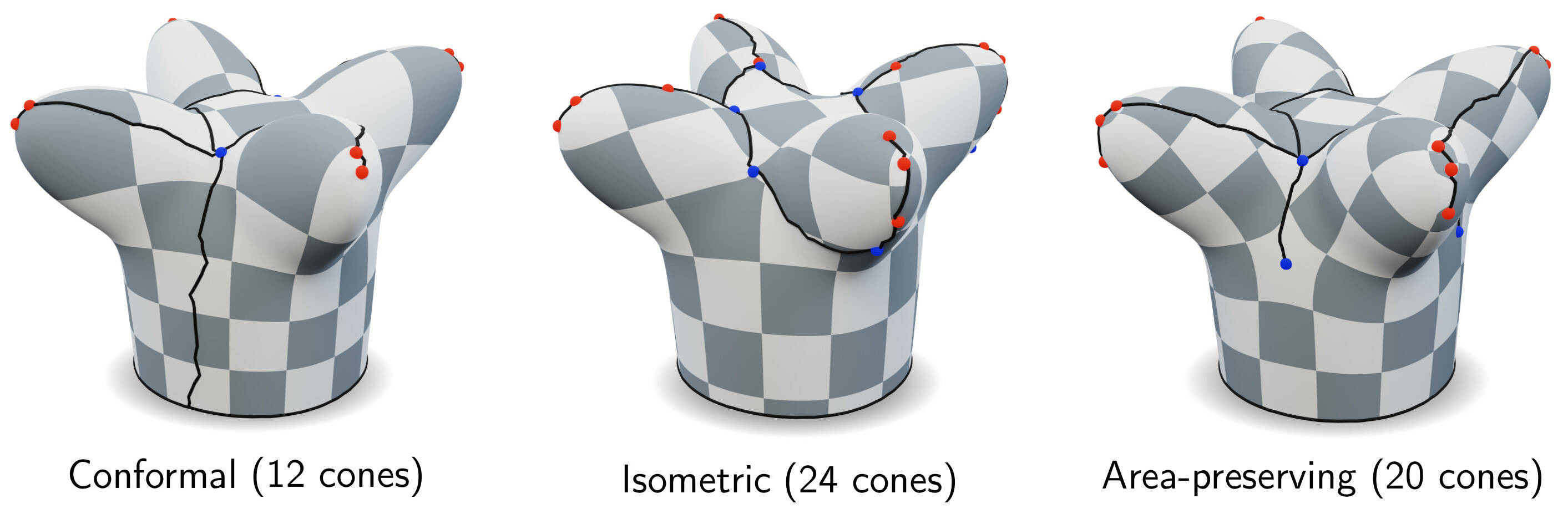

as we can see on Fig. 6 (and on the representative image on top of the page), minimizing those different criteria lead to a different placement of cones. In other words, we were able to influence the distribution of singularity cones in order to better minimize the distortion of the parametrization.

Figure 6. Optimization of the same model while minimizing different distortion criteria. The optimization yields different cone distributions whether we optimize for an angle-preserving (conformal) or area-preserving mapping.

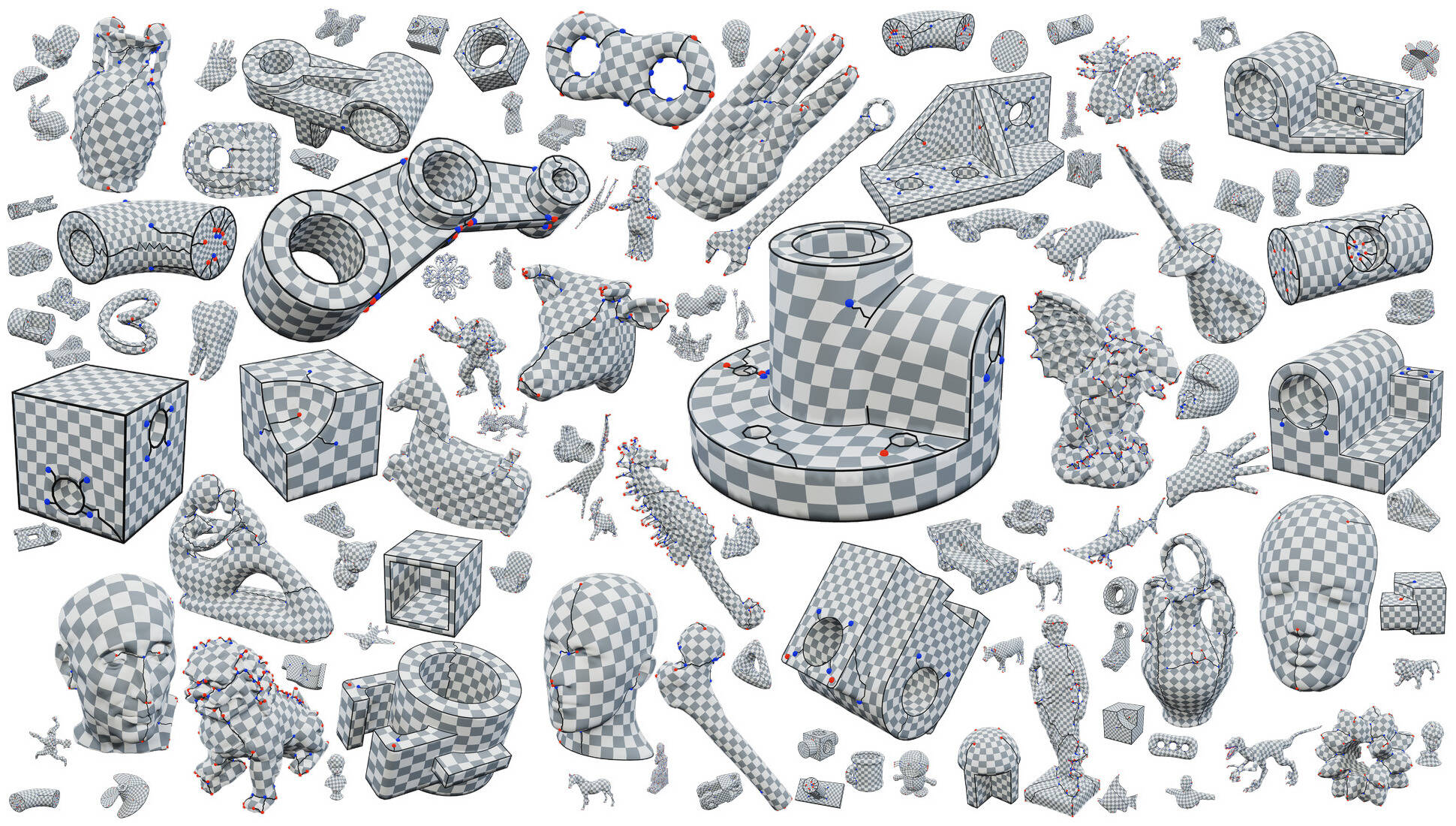

Gallery of results

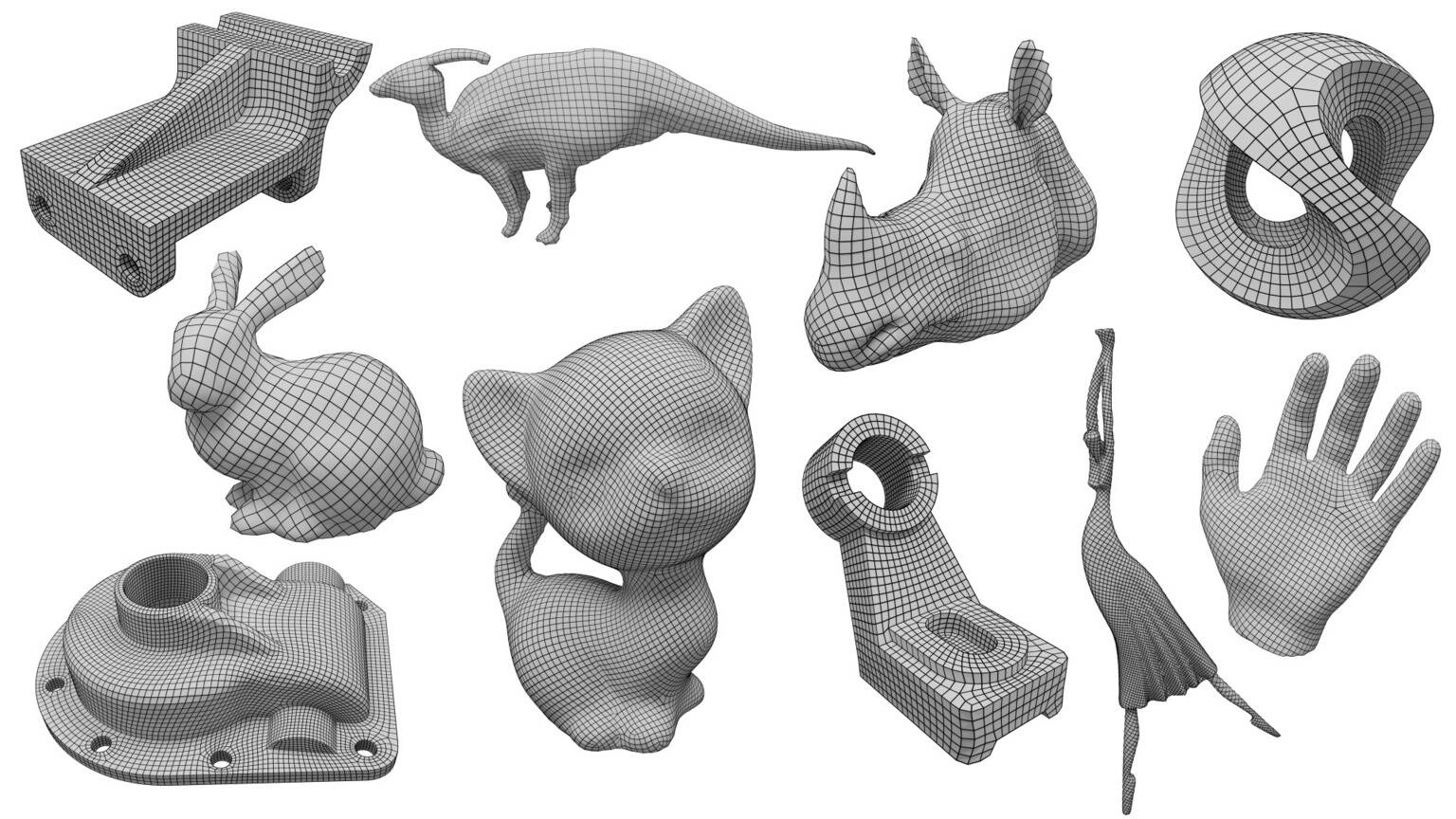

Figure 7. Gallery of results on a variety of models.

Figure 8. Gallery of quadmeshes obtained using our parametrization algorithm.

BibTeX

@article{coiffier2023movingframes,

author = {Coiffier, Guillaume and Corman, Etienne},

title = {The Method of Moving Frames for Surface Global Parametrization},

year = {2023},

issue_date = {October 2023},

publisher = {Association for Computing Machinery},

volume = {42},

number = {5},

issn = {0730-0301},

url = {https://doi.org/10.1145/3604282},

doi = {10.1145/3604282},

journal = {ACM Trans. Graph.},

month = {sep},

articleno = {166},

numpages = {18}

}